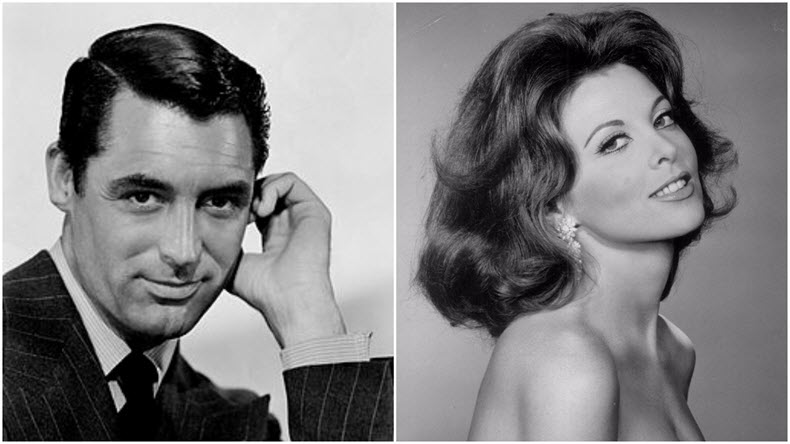

I used to joke that the worst moment of my life was when I realized I would never be Cary Grant. At fifteen years old I sat in my family’s TV room watching Alfred Hitchcock’s classic North by Northwest not just with pleasure but with a vague anxiety that I did not immediately understand. Of course by then I had long suspected I would never be as tall or as good looking as Cary Grant. Still, in my mind lived the image of the adult male I was supposed to become: confident, socially adept, a high earner, and yet still self-deprecating. In other words, Roger O. Thornhill, the suave adman that Cary Grant played. But what magic would transform my insecure adolescent self into that man?

The Cary Grant ideal self who lived in my 15-year old head is what psychotherapy calls an introject — an idea swallowed whole from the outside world. Introjects come in many shapes and sizes. They might come from ads, tv shows, and social media, repeated images of what you and your life should be like or ways in which you don’t measure up. They might be repeated messages from a parent, telling you that you are bad or selfish for wanting more than you have. Often, introjects are rooted in inferences that you don’t even know you are making. For example, did your parents bluntly state that world was too dangerous for you to be taking risks? That you weren’t up to a particular challenge? Or do you just feel like they did?

Like having any goal, having an ideal self isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The problem with introjects has do with issues of awareness and choice. Sometimes, we are unaware of the internal voices that judge whether we are good or bad, pretty or ugly, successful or failed, and that tell us what we should do or not do. Often, even if we are aware of these voices we think we have chosen the rules, judgements and goals that they espouse. This is a problem. If we are unaware of an attitude, how can we evaluate or challenge it? If we think an idea is an essential chosen part of our identity, why would we change it? And if outside or unconscious standards of success or beauty or worth drive us, how will we ever be enough?

Uncovering and challenging introjects is a powerful tool in psychotherapy. To see if a self-judgment or repeated thought is an introject, you might ask yourself: “Who is saying this?” Even better, you might say the repeated thought out loud. For example, you might say, “Before you can do x (go for this job, start dating, be proud of myself) you need to do or be y (have this accomplishment, be more fit, have this much money).” And then ask yourself, “Who is saying this? If not me, who?” This process, the giving of voice to what has been silent or shameful, is at the heart of psychotherapy. It is part of the reason that the client-therapist dialogue is so important.

“Who is saying this?” is a simple question. But the process of uprooting introjects is not easy. In North by Northwest, Cary Grant is mistaken for an FBI agent and must go on the run. Grant is faced with all sorts of trials, including driving after being forcefed several quarts of spirits, eluding a plane that’s trying to cropdust him to death, and fleeing across the face of Mt. Rushmore. Through it all Grant retains his humor, dignity, and even manages to look crisp despite having only the suit and shirt on his back. Even at 15, I knew this was a ridiculous standard to aspire to. What I was unaware of were all of the introjected shoulds that made me admire Grant’s character. And how those introjects, those unchosen intruders masked as my own internal voices, could and would fuel self-criticism that would stand in the way of discovering my true attitudes, desires, and values.